The Climate Impact of Suburbanization

- Housing choice is inextricably linked to climate impact. Among all large metros in the U.S., the average household carbon footprint is 18 percent higher in suburban “fringe” counties compared to more urban “central” counties. Prioritizing dense, transit-oriented, and walkable development is crucial to meeting climate goals.

- Unfortunately, the pandemic may be pushing us in the opposite direction, as the rise of remote work and worsening affordability concerns push many households to the further reaches of large metros.

- From 2019 to 2021, the fringe counties of large metros saw their populations grow by 2.4 percent, while central counties grew by just 0.1 percent. And the counties that encompass some of the nation’s densest cities actually lost significant population over this period, including San Francisco (-7.5 percent), Washington, D.C., (-5.1 percent), and Boston (-4.1 percent).

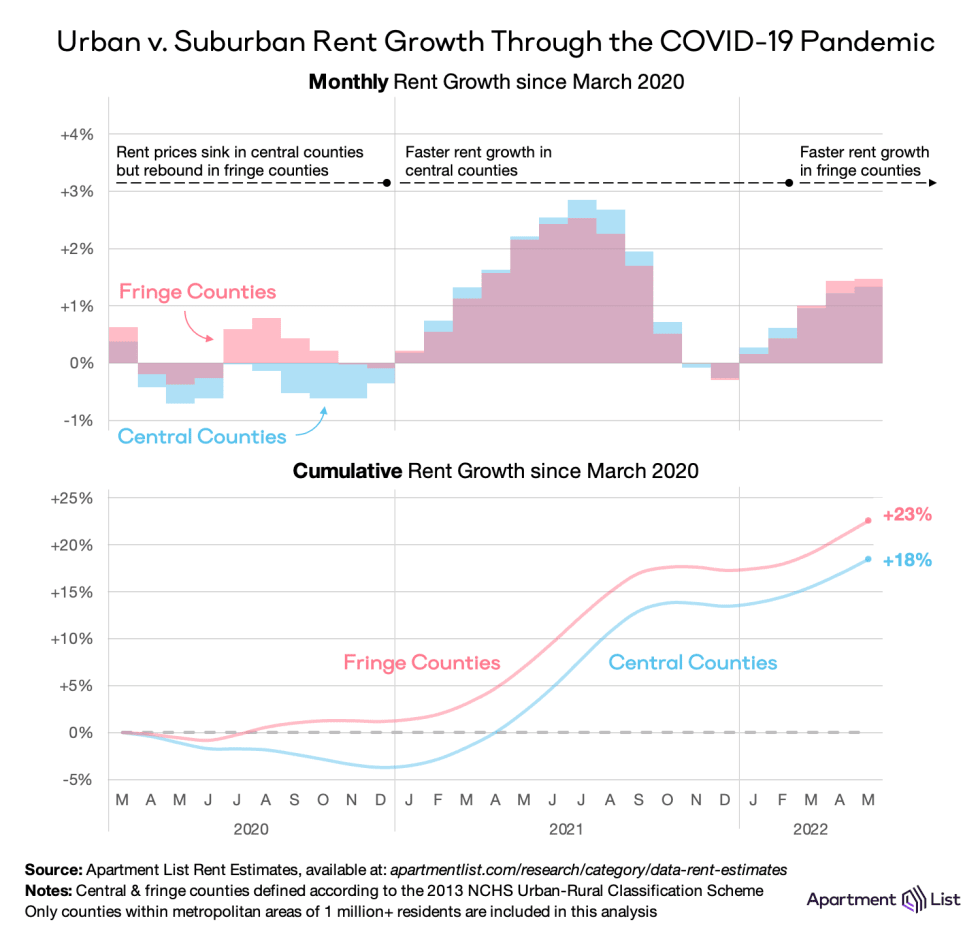

- Looking at our Apartment List rent estimates as a more timely proxy for housing demand, we observe a similar trend – from March 2020 through May 2022, rents in fringe counties have increased by 23 percent, compared to 18 percent in central counties.

- In some metros, this trend has been even more pronounced than the national average. We present a sample of these as case studies below, visualizing the trend in a series of maps.

- Despite this trend, the strong rebound in urban rents suggests that city living still maintains broad appeal, and increasing supply in the right places could make lower-impact urban living more accessible.

Introduction

In just the past week, extreme heat has broken records in cities across the U.S., and severe flooding has closed one the country’s most popular national parks. The effects of climate change are already upon us, and addressing this global crisis is undeniable among the most pressing issues of our time. Housing is inextricably linked to the climate, and the way that we organize our cities has a profound impact on our carbon footprints. In densely populated urban areas – in which individuals occupy less space and are less reliant on cars – per-capita emissions are significantly lower than they are in the surrounding suburbs, where cars are typically the dominant commute mode and residents often bear long drives in traffic to access jobs in the city. Given this dynamic, it is crucial that we grow our nation’s population centers in ways that prioritize dense, transit-oriented development.

Unfortunately, the pandemic appears to be pushing us in the opposite direction. Remote work has made proximity to the office a less pressing concern and enabled more people to move further from job centers. At the same time, skyrocketing prices on both the rental and for sale sides of the market have pushed many households to expand their searches further from the urban core, where housing tends to be more affordable. As a result, demand for rentals has been strongest in the suburbs of large metros, with the potential to drive precisely the type of sprawl that is at odds with progress on emissions.

In America’s major metropolitan areas, rental demand has been strongest in the high emission suburbs

In order to better understand how climate impacts vary across large cities and their suburbs, we rely on county-level estimates of [average household-level carbon footprints](Jones, C.; Kammen, D. M. Spatial Distribution of U.S. Household Carbon Footprints Reveals Suburbanization Undermines Greenhouse Gas Benefits of Urban Population Density. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2014, 48, 2, 895–902.) produced by Christopher Jones and Daniel M. Kammen at the University of California Berkeley.1 We then map counties to their respective metropolitan areas and place them into two categories – “central” and “fringe” – according to definitions from the U.S. Census Bureau. We focus here on large metropolitan areas with at least 1 million residents. The central counties are those which contain the metro’s principal cities, while all other counties are considered fringe.2

Across all 56 large metropolitan areas in the U.S., the average household carbon footprint is 18 percent higher in fringe counties compared to central ones (54.1 tons of carbon dioxide equivalent per year (tCO2e/yr) vs 45.8). The climate benefits of urban living can be seen even more clearly in the nation’s densest counties. For example, in New York County (i.e. Manhattan) the average household has a carbon footprint of just 32.6 tCO2e/yr, while in the fringe counties of the New York City metro, the average footprint is 68 percent greater (54.1 tCO2e/yr). While there are a variety of factors that contribute to the lower carbon footprints of urban residents, a key factor is that they tend to drive less – the average household in a fringe county drives 41 percent more miles per year than the average household in a central county. Promoting this type of dense, transit-oriented, and walkable living should be a key part of climate change mitigation strategies.

But in the decade preceding the pandemic (2010 to 2019), the fringe counties of large metros grew slightly faster than the denser central counties (8.3 percent vs 7.8 percent). And more recently, this trend appears to be accelerating. From 2019 to 2021, Census data shows that the fringe counties grew by 2.4 percent while central counties grew by just 0.1 percent. In fact, many of the nation’s most dense, walkable cities actually saw a significant loss of population over this period. In the counties that are home to San Francisco, Washington, D.C., and Boston, populations fell by 7.5 percent, 5.1 percent, and 4.1 percent, respectively, from 2019 to 2021.

More recent Census data on population trends is not yet available, but our Apartment List rent estimates can serve as a more timely proxy for housing demand.3 Trends in rent growth confirm that suburbs have been booming throughout the pandemic:

This played out most starkly in the first year of the pandemic, when large numbers of renters gave up leases in pricey coastal cities amid lockdowns and widespread economic uncertainty. From March to December 2020, rents in the central counties of large metros fell by 3.7 percent while in the fringe counties they rose by 1.2 percent. This gap shrank somewhat last year as the urban cores of many large metros experienced strong rebounds, but has more recently started to widen again. After the rapid price increases which have disrupted nearly all major rental markets in 2021 and 2022, aggregate rent growth since the start of the pandemic now stands at 18 percent in central counties compared to 23 percent in fringe ones. Amid rapidly rising housing costs and a broader inflationary environment, and with remote work continuing to take hold, it’s possible that rental demand will continue to shift toward the high-emitting suburbs as Americans seek out areas where they can get more space for less money, even if it means being further from the city.

This trend can perhaps be seen most clearly by visualizing average household carbon footprints side-by-side with pandemic-era rent growth. We do so below for a handful of major markets:

Washington, D.C.

In Washington, D.C., the average household carbon footprint is 38 tCO2e/yr, ranking among the lowest per-capita emissions rates in the country. The neighboring northern VA counties of Arlington and Alexandria are also considered central, giving the D.C. metro’s central counties an overall household emissions rate of 43 tCO2e/yr. In the surrounding fringe counties that comprise the rest of the metro, the rate is 34% higher at 57.8 tCO2e/yr. Per-capita emissions are highest in the counties that are furthest removed from the urban core. For example, the highest average household emissions in the metro are found in Loudoun County, VA (64.8 tCO2e/yr).

High emissions rates in the metro’s fringe counties are at least partially attributable to long traffic-laden commutes from the suburbs to the city. In fact, the D.C. metro is also one of the nation’s epicenters of the growing trend of “super commuting,” whereby individuals bear commutes of 90 or more minutes each way to work. And with D.C. proper ranking among the nation's most expensive housing markets, demand is continuing to shift toward these outlying areas. D.C. saw one of the sharpest rent declines in 2020, and despite having fully made up that lost ground, rents there are still just 3.6 percent higher than their March 2020 level. Meanwhile, the surrounding suburbs in Northern VA and Maralynd have boomed, with rents up by 18.1 percent since the start of the pandemic.

Boston

In the central Suffolk County of the Boston metro, average household emissions are 28 percent lower than in the surrounding fringe counties. But from 2019 to 2021, Census data shows that the central county lost 4.1 percent of its population, while the fringe counties grew by 1.5 percent. A strong rebound in rents indicates that the urban core is likely now gaining back that lost population, but over the full course of the pandemic, rents in the central county are up by just 5.6 percent, compared to 19.4 percent in the surrounding fringe counties.

In fact, some of the strongest rental demand in the region has actually been beyond the traditional bounds of the metro. In Worcester County, MA rents are up by 29.6 percent since the start of the pandemic, and Hillsborough County, NH has seen an even sharper increase of 34.3 percent. Current Census definitions consider these counties to be distinct medium-sized metros anchored by Worcester, MA and Manchester, NH, respectively, but it’s likely that the recent surge in demand in these areas has been driven by folks whose jobs are located in and around Boston. With more companies signaling that hybrid remote work is here to stay, we could be seeing a gradual expansion of traditional metro boundaries. Longer commute times may seem more bearable if they only need to be undertaken two days per week.

Atlanta

Atlanta, is known to be a fairly car-dependent city, but even here we see that the central county maintains a notable emissions advantage over the surrounding fringe counties, with the average household carbon footprint being 11 percent higher in the fringe counties. Atlanta also differs from the examples above in that the core city did not experience any meaningful early-pandemic rent decline. Rather, the broader Atlanta metro has boomed throughout the pandemic, ranking #14 for metro-wide rent growth since March 2020 among metros with a population over 1 million. But here again, that rapid growth has been most concentrated in the suburbs. The central county has seen rents increase by 20.2 percent since March 2020, roughly in line with the national average, while the fringe counties have experienced a staggering increase of 36.3 percent.

Denver

Denver had been a booming market since well before the pandemic, with much of that growth centered in the urban core. The population of the metro’s central county increased by 20.5 percent percent from 2010 to 2019, significantly faster than the 14.8 percent growth in the fringe counties. However, from 2019 to 2021, the population of the metro’s central county actually fell by 2.2 percent, while the population of the fringe counties ticked up by 0.9 percent. Our rent estimates also show stronger demand in Denver’s suburbs in recent years, with the median rent in fringe counties up by 21.9 percent since the start of the pandemic, compared to an increase of just 12.1 percent in the central county.

New York City

The nation’s largest metro experienced a clear flight from the urban core during the onset of the pandemic, and with it came one of the nation’s sharpest rent declines: 20 percent from March through December 2020. More recently, however, the city has also experienced one of the nation’s strongest rebounds. In fact, New York City currently has the fastest year-over-year rent growth among the 100 largest cities in the U.S., (+29.5 percent), clearly demonstrating that big city living maintains an enduring appeal. Rent growth over the course of the entire pandemic has still been faster in the metro’s fringe counties compared to its central ones, but over the past year, that relationship has inverted, with the central counties seeing stronger rental demand. Here at least, it appears that a shift toward the suburbs may have been a temporary pandemic-driven phenomenon, rather than a long-term trend

Conclusion

Over the past two years, pandemic-related changes in where we live and how we work have driven an increased demand for space and affordability, even if it means sacrificing urban amenities. This trend has shown up clearly in our rent data, with the fringe counties of large metros experiencing notably faster rent growth than the central ones. However, this shift toward the suburbs has negative implications for the climate, as suburban households have significantly higher carbon footprints, on average, than their counterparts in the urban core. And while remote work might eliminate some commutes, it could also push some part-time commuters to move even further from their jobs. Crucially, this flight to the further reaches of large metros is not driven purely by preference, but largely by affordability – a lack of new construction has made housing in the urban core prohibitively expensive in many cases. The sharp rebound of the New York City rental market makes clear that the excitement of city living still maintains a strong appeal. With housing affordability having reached crisis levels across the country, it’s crucial that we not only grow our nation’s housing supply, but do so in a sustainable way.

- Jones, C.; Kammen, D. M. Spatial Distribution of U.S. Household Carbon Footprints Reveals Suburbanization Undermines Greenhouse Gas Benefits of Urban Population Density. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2014, 48, 2, 895–902.↩

- To be more specific, Census makes the delineation between central and fringe counties only for metropolitan areas with at least 1 million residents. Central means the county 1) contains the entire population of the metro's largest principal city or 2) is completely contained within the metro's largest principal city, or 3) contains at least 250,000 residents of any principal city within the metro. Fringe refers to all other counties in the metro that do not qualify as central. Note that some metros contain multiple central counties.↩

- Over the short run, housing supply in a given location is relatively fixed, and so a surge in demand (i.e. more households looking to buy or rent) tends to push up prices. A complete picture of housing price appreciation is somewhat more nuanced, but in general, rapidly increasing prices suggest an influx of new households to a given market. Our estimates capture only the rental side of the market, but markets that are seeing strong demand for rentals also tend to be hot for-sale markets.↩

Share this Article