New Housing Construction Continues to Lag: Building Permits vs. Job Growth 2019

- In 2018, the total number of new housing units permitted in the U.S. increased to 1.32 million. Planned construction has rebounded since the great recession but remains 38.2 percent below the pre-recession peak. The lowered level of new construction is being driven by a lack of new single-family housing, while the number of multi-family permits surpassed its pre-recession peak in 2015.

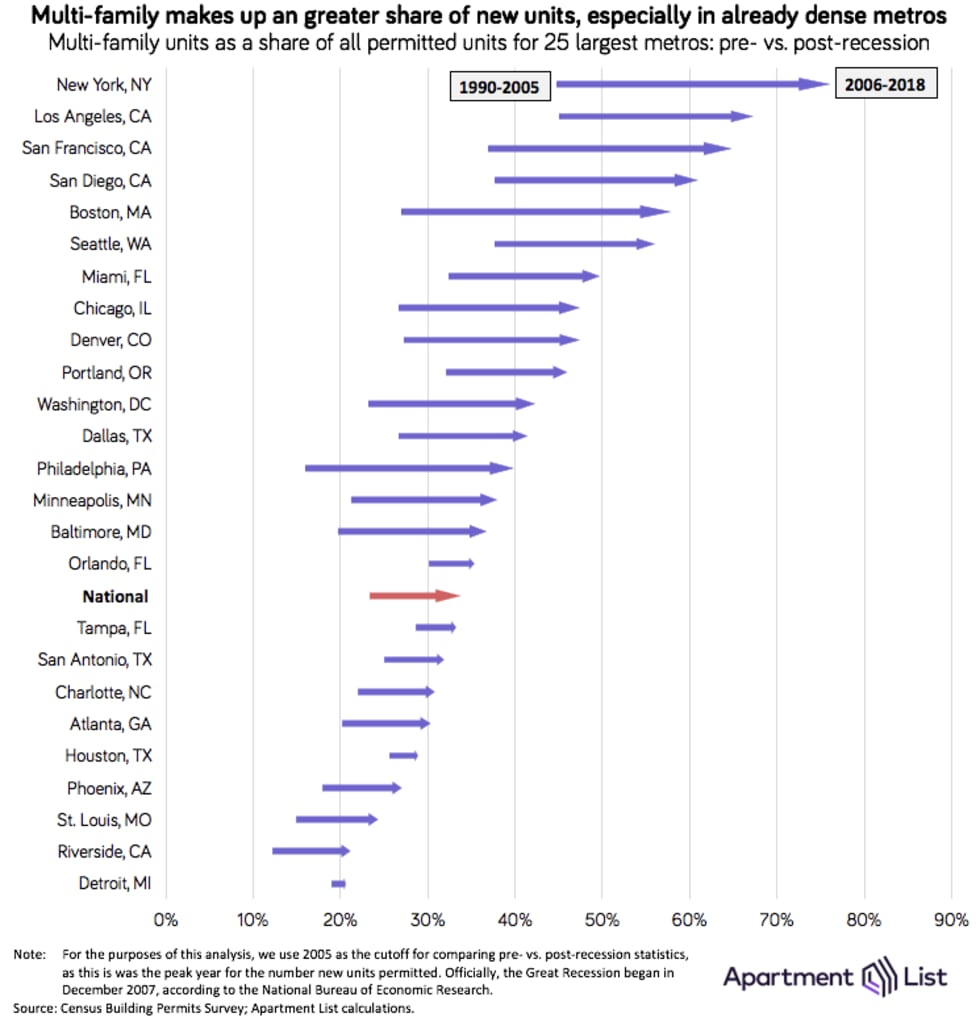

- While multi-family is making up a greater share of new construction in all of the nation’s largest markets, the biggest increases in the multi-family share have occurred in already dense metros such as New York, Boston and San Francisco. Notably, these metros have also suffered from a severe lack of affordability that has sparked fierce debate about how to maintain inclusivity in the superstar cities that drive the modern economy.

- In many of the nation’s fast-growing Sun Belt metros, more than two-in-three new housing units are still single-family homes. While most of these metros have built enough new housing to keep pace with strong job growth, they have done so primarily through continued single-family sprawl.

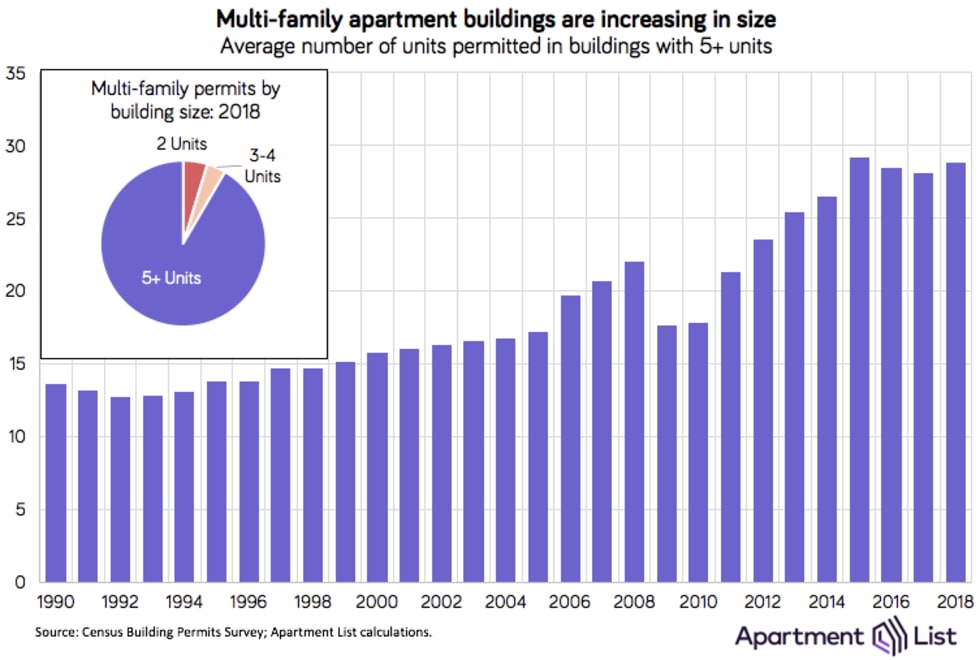

- These disparate patterns of residential development are playing out at a time when housing experts and policy makers across the country are advocating zoning reforms aimed at enabling dense, transit-oriented development. While small two to four unit buildings are crucial to creating dense walkable neighborhoods outside the downtown core, we find that developers are building larger multi-family properties each year.

Download Local Metro and County Level Data

Introduction

In May 2009, shortly before the official end of the Great Recession, the number of housing units authorized by newly issued building permits hit its lowest level since the Census Bureau began tracking the data in 1960. More than a decade later, the pace of new construction remains significantly below its pre-recession peak, with 38.3 percent fewer units permitted in 2018 than in 2005.

Meanwhile, housing affordability has emerged as a key issue in national politics, as millions of American households struggle with their housing costs. That said, housing and labor markets are inherently local, and distinct trends are playing out in different regions of the county. In many of the nation’s largest coastal metros, acute housing shortages have led to rapid increases in housing costs. However, many smaller metros are actually adding more than enough new housing to keep pace with job growth, indicating that affordability issues in these regions may be driven more by a lack of well-paid jobs than by a shortage of housing.

In order to better understand these issues, we analyzed data from the Census and Bureau of Labor Statistics to better understand how much new housing is being built and where. We study how that new housing supply lines up with job growth for counties and metro areas across the U.S., and discuss how these findings fit within the broader conversation around housing affordability across America.

Number of housing permits issued remain well-below pre-recession peak, driven by a lack of new single-family homes

Prior to the Great Recession, the number of new housing units permitted in the U.S. had been on a steady upward trajectory for fifteen years, increasing from 1.12 million in 1990 to a pre-recession peak of 2.16 million in 2005. Most of these new housing units came from a boom in single-family home construction. From 1990 to 2005, the number of single-family permits issued more than doubled, while the number of multi-family permits grew by 49 percent.

As the national housing market collapsed amidst the subprime mortgage crisis, new construction ground to a halt, with building permit issuance bottoming out at the lowest level ever recorded in 2009. In the recovery years that followed, multi-family housing construction rebounded fairly quickly, driven by a trend toward urbanization that increased demand for housing in and around city centers. The number of multi-family units permitted surpassed its pre-recession peak in 2015 and has since maintained that pace.

Meanwhile, construction of single-family homes has recovered much more slowly -- the number of single-family housing units permitted in 2018 was barely half the number permitted in 2005. Consequently, multi-family units have made up a much greater share of new housing in the post-recession period. From 1990 to 2005, multi-family units made up 23.4 percent of all residential building permits issued, while from 2006 to 2018, that share increased to 33.9 percent.

Despite the boom in apartment construction, multi-family housing has not been able to fully compensate for the lack of new single-family construction. The total number of residential housing units permitted in 2018 was roughly the same as the number permitted in 1994, when the country’s population was 20 percent less than it is today. While multi-family housing may be better suited to meet the demand for walkable, transit-oriented neighborhoods, local zoning codes severely limit the locations where multi-family housing can be built. Consequently, the slowdown in single-family construction has contributed to a tightening of starter home inventory, which may be preventing some prospective millennial homebuyers from purchasing homes.

Multi-family share increasing fastest in the places where it was already high

The increase in the share of residential building permits comprised of multi-family units is a trend that holds true not just at the national level, but in each of the nation’s 25 largest metro areas.

While the multi-family category made up a greater share of new housing in all of the 25 largest metros, the size of the increase varies dramatically. The biggest jumps in the multi-family share have occurred in the nation’s densest metros, places that had already been building a significant amount of multi-family. The New York City metro experienced the biggest jump. In the pre-recession years from 1990 to 2005, multi-family comprised 44.8 percent of all building permits issued in the New York City metro -- then the second highest share among the 25 largest metros -- and in the post-recession years from 2006 to 2018, that share spiked to 76.3.

We see similarly large increases in other dense coastal metros, with Boston, San Francisco, Philadelphia, and San Diego rounding out the top five list for metros with the largest increases in the multi-family permit share. Notably, Philadelphia is the only metro among those five that has built enough new housing over the past decade to keep pace with job growth, according to our jobs-per-permit metric, and as a result has seen relative stability in their housing market.

New housing shortages mostly confined to coastal metros

In a balanced market, a new housing unit should be built for every one to two new jobs that the economy adds. Markets that add more than two jobs-per-permit are considered to be undersupplied. Using data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics, we estimate that the Bay Area has the nation’s most acute housing shortage, resulting in soaring housing costs.

Since 2008, the San Francisco metro has added 3.45 jobs for every new housing unit permitted, more than any other large metro in the nation. Furthermore, when we zoom in to the county level, we find that this housing is not being built in the same locations where jobs are being created. San Francisco County accounted for 45.6 percent of job growth in the five-county metro area, but just 28.3 percent of new housing units permitted, resulting in a staggering 5.56 jobs-per-permit. The fact that the region’s housing shortage is most acute in the urban core has led to some of the nation’s longest commute times.

As mentioned above, we observe similar trends in the New York City, Boston, and San Diego metros, which all added more than two jobs-per-permit from 2008 to 2018. These supply-constrained markets are also well known for being among the nation’s most expensive, demonstrating the fundamental relationship between supply, demand, and price.

That said, acute shortages of new housing seem to be mostly confined to this relatively small but populous set of coastal hubs. In fact, many smaller metros throughout the country are actually building more new housing than needed based on local job growth. As the knowledge jobs of the modern economy cluster in a shrinking set of “superstar cities,” job growth has lagged in many other parts of the country. In these regions, it seems that struggles with housing affordability may have more to do with household income than with housing supply.

That said, there are a subset of metro areas that are thriving economically and building sufficient new housing to keep pace with job growth. This group is primarily comprised of Sun Belt metros such as Phoenix, Dallas, Atlanta, and Charlotte. Notably, single-family is still the dominant type of new housing being built in these metros, and while the multi-family share is on the rise in these regions, the increases are much more muted than those observed in the dense coastal metros discussed above. In Phoenix, for example, single-family accounted for nearly three-in-four new housing units permitted from 2006 to 2018. It seems that the metros most effectively meeting the demand for new housing are still primarily doing so by continuing to sprawl, despite an increasing demand for dense, walkable neighborhoods that prioritize sustainability.

In new multi-family construction the “missing middle” is still missing

These disparate patterns of residential development are playing out at a time when single-family housing has begun to face unprecedented criticism from both housing experts and policy makers. For the latter half of the 20th century, suburban single-family homes were synonymous with the popular understanding of the “American Dream.”

In recent years, however, a more nuanced view has emerged, which acknowledges that single-family zoning policies were often inextricably linked to redlining practices that served to explicitly enforce patterns of residential racial segregation. Single-family zoning also impedes the development of dense multi-family housing units, which can be an important source of market-rate affordable housing. Furthermore, denser cities are significantly more sustainable, and growing our cities with more dense development can play an important role in combating climate change.

Consequently, policy makers across the country are making efforts to enable multi-family development in areas that were previously reserved for single-family homes. In 2018, an ambitious set of zoning reforms known as Minneapolis 2040 upzoned half of that city’s land in a way that aims to explicitly address patterns of racial and economic inequality. The city of Seattle also recently eliminated single-family zoning in a subset of its neighborhoods, and a statewide upzoning bill in Oregon was passed just this month. In California, where the housing shortage is most acute, the upzoning bill SB 50 is currently stalled in the state senate, awaiting a vote next year.

Many of the zoning reforms described above strive to remove barriers to building a type of housing that has been referred to as the “missing middle.” This type of housing -- two to four unit buildings, accessory dwelling units, townhouses, and low-rise apartment buildings -- can play an important role in increasing density and creating walkable neighborhoods, without impacting neighborhood character is the same way as mid- and high-rise apartment buildings. Despite the benefits of this type of housing, the multi-family housing that has been built in recent years increasingly takes the form of large apartment complexes.

We find that two to four unit properties made up just 3.0 percent of all housing units permitted in 2018. That share has been on a downward trajectory since 1990, when duplexes, triplexes, and fourplexes comprised 4.9 percent of residential permits. Two to four unit properties account for 8.0 percent of the nation’s total housing stock, indicating that this type of construction was far more prevalent in the past. Meanwhile, buildings with five or more units accounted for 91.6 percent of multi-family units permitted in 2018, and the average size of these properties has been steadily increasing. In 1990, the average number of units in buildings with five or more units was 13.6, but by 2018 that average building size more than doubled to 28.7.

While these large multi-family developments are an important form of new housing supply, they are usually confined to locations in and around the downtown areas of major cities. Due to high construction costs -- for land, labor, materials, and regulatory costs -- developers build larger properties at luxury price points in order to achieve economies of scale and ensure that projects prove profitable. Zoning reform can remove bureaucratic hurdles to allow denser development in varying forms throughout a metro area.

Conclusion

As millions of Americans struggle with housing costs, the issue has come to take center stage in both national and local politics. A number of 2020 Democratic frontrunners have issued policy platforms that address housing affordability, while cities and states across the country have begun to debate and enact fundamental reforms to their zoning codes.

Much of this debate has centered on the need for dense, transit-oriented development in our nation’s cities. Dense housing plays an important role in maintaining inclusive housing affordability and cities developed in this manner are also significantly more environmentally sustainable.

While we find that proportionally more multi-family housing has been built in recent years, the metros where it is most prevalent tend to be the coastal superstar cities that have struggled to build enough new housing overall. Meanwhile, fast-growing Sun Belt metros have continued to rely on single-family homes to maintain sufficient housing supply. These contrasting trends emphasize that decisions around what type of housing gets built and where are crucial to determining the future of America’s cities.

Download Local Metro and County Level Data

Share this Article