Renters and Voting

Apartment List recently released a report looking at how the housing market has changed since the recession. A key finding from our analysis was that the cost of homeownership has declined significantly since the recession, even as rents continue to climb in many metros. Homeowners have benefited significantly from low interest rates and mortgage tax deductions, while renters (especially on the low end of the housing market) struggle with affordability.

Why is this the case? One possible reason is because renters are much less likely to vote. They tend to be younger, more transient, and less politically engaged; as a result, their influence in the political process is diminished. Today, we dive further into this issue, examining the key policies that benefit homeowners and renters, as well as the data behind renter and owner voting patterns, to gain a better understanding as we head into the upcoming election.

Homeowners benefit from a range of tax deductions

Homeownership has long been part of the American Dream, and policy- and law-makers have done their part to contribute to this, creating a number of tax deductions that incentivize homeownership. Various opinions and articles have been written on all of these different deductions, but the bottom line is that homeowners are rewarded simply for being homeowners. Homeowner benefits include the following:

- Deductions for the property tax paid on a home

- Exclusions of up to $250,000 or $500,000 (in the case of joint filers) of capital gains from taxable income after a home sale

- Tax deductions for all costs involved in making a sale

- Deductions on interest for loans that are taken out to substantially improve a home's value

- Exclusions of imputed rental income, which is the investment return that homeowners gain from living in their homes rent-free

- The mortgage interest tax deduction.

The benefits available to homeowners can extend to second home purchases as well. According to the IRS, when it comes to mortgage tax deductions a second home can be a house, condo, co-op, mobile home, house trailer, or boat, that has cooking, sleeping, and toilet facilities. If a homeowner rents out their second home to help bring in some income, they must use the home themselves for 14 days (or more than 10% of the days) out of the year in order for it to qualify. Priceonomics recently illustrated an example of how the mortgage tax deduction can benefit homeowners in this type of situation:

Now consider the case of a father of two who makes $200,000 a year and is buying a million dollar lake house. (Individuals can typically claim the mortgage interest deduction on up to two homes for a tax break worth up to $1.1 million.) Mike pays a 28% federal income tax rate, which means that he can deduct 28% of his $32,200 annual payments. That comes out to $9,020.

These deductions can add up to a pretty hefty pay-out, and do their part in incentivizing more people to buy homes. Renters, on the other hand, qualify for almost no tax deductions. They can deduct property taxes if they're required to pay them as part of the lease, and in some states renters can receive credits or refunds.1 But there are no overarching tax deductions for which all renters can qualify, just by virtue of the fact that they are renting. If a renter is in a position to benefit from tax deductions, they often have to meet certain requirements in order to qualify.2 These largely vary by state, with most states not providing these benefits for renters.

There's little public benefit in homeownership

While homeownership can be a gateway for American families to accumulate wealth, artificially boosting the homeownership rate by offering tax benefits can cause a number of negative side effects. Purchasing a home exposes families to fluctuations in home prices, and families without stable employment can lose their home through foreclosure. Also, owners are less geographically mobile, making the labor market less flexible. Renters, on the other hand, find it easier to move to cities with better employment opportunities.

Increasingly, there is consensus among economists that current policies artificially distort the housing market. Edward Glaesar, the Glimp professor of economics at Harvard University, argues that we should worry about high housing costs, not low homeownership rates:

There is little public benefit in pushing people to own rather than rent homes, just as there is little public benefit is squelching the market for leased cars. Homeowners are somewhat better citizens, but we shouldn’t screw up the $28 trillion housing market in the hopes of mildly increasing engagement in local politics. Moreover, when homeowners get involved in politics, they often try to stop new development which makes housing less affordable for everyone else.

Homeowners who pay off their mortgages or who are lucky enough to experience rising housing prices do become wealthier. But making it easier to borrow reduces the need to save for a down-payment, and owners can also be hit by falling prices.

Subsidizing homeownership has bad side effects. Owners are less mobile, which makes it harder for them to move from high unemployment places to high wage places.

Although many hold homeownership to be a key part of the American Dream, its actual benefits to society may not be as clear-cut as some make it out to be.

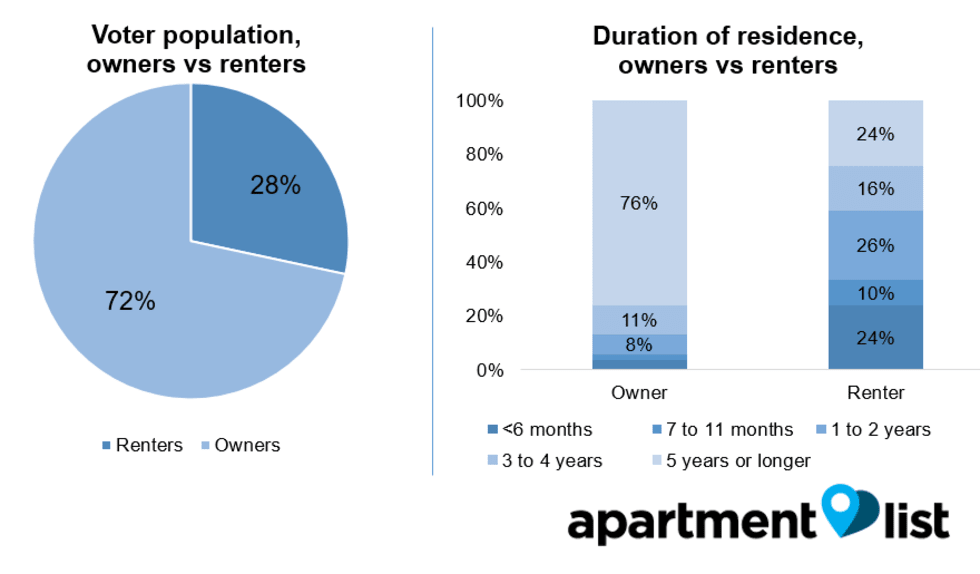

Renters form only 28% of the voter population, and are much more transient

So, why do homeowners receive more benefits than renters? A big part of this may be because they aren't as involved in the political process. To better understand this issue, we dive into Census data on renter/owner voting patterns.

According to Census data from 2012, renters only form 28% of the voter population. They also tend to be much more transient: 59% of renters have lived in their current residence for less than 2 years, whereas 76% of owners have lived there for more than 5 years. Long-term residents are more likely to feel invested in their area and vote.

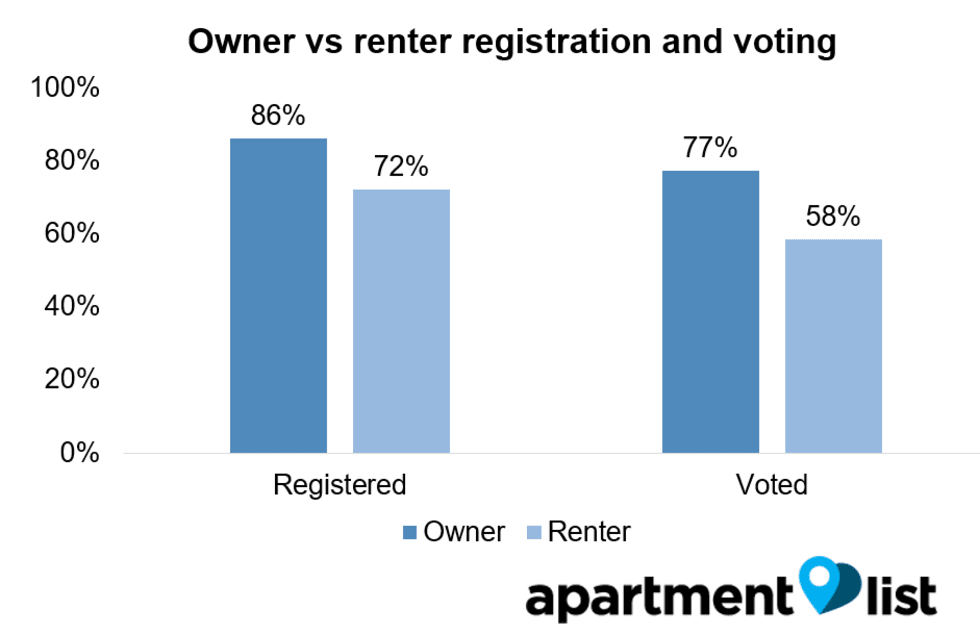

Homeowners are much more likely to register and vote

Because renters are so transient, they are significantly less likely to register to vote, or to actually vote. 77% of homeowners vote, compared to only 58% of renters - in other words, homeowners are 25% more likely to make their voice heard in an election.

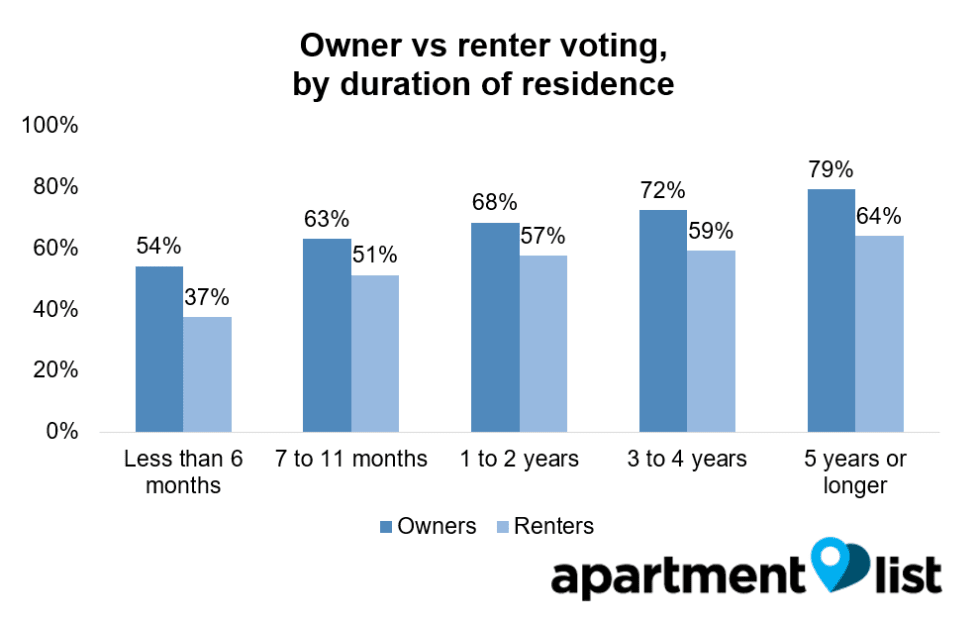

Even controlling for duration of residence, renters are less likely to vote

Even when controlling for duration of residence, renters are significantly less likely to vote. Strikingly, an owner who has lived in his or her home for 1-2 years is more likely to vote than a renter who has been there for more than 5 years.

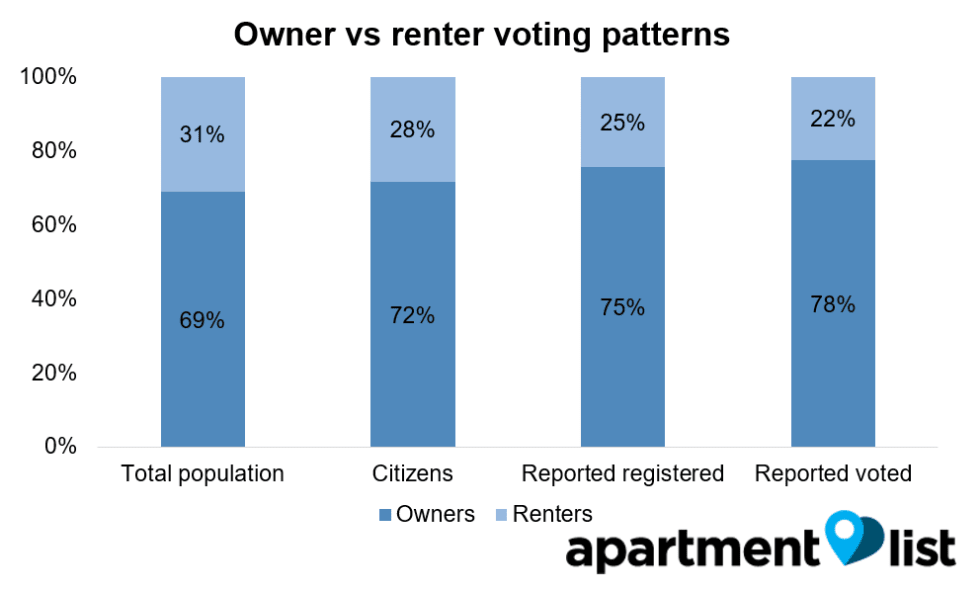

Renters punch below their weight in elections

Because of this, renters tend to punch below their weight in elections. They form 31% of the overall population, but since immigrants are more likely to be renters, only 28% of citizens are renters. Because fewer renters register and actually vote, they only form 25% of registered voters and 22% of actual voters. No wonder their voices are not being heard!

Because of this, renters tend to punch below their weight in elections. They form 31% of the overall population, but since immigrants are more likely to be renters, only 28% of citizens are renters. Because fewer renters register and actually vote, they only form 25% of registered voters and 22% of actual voters. No wonder their voices are not being heard!

Despite the relatively low voter turnout rate among renters, there are a few trends that suggest that renters' voice may increasingly be heard in the coming years.

The renter population is growing more rapidly than the owner population

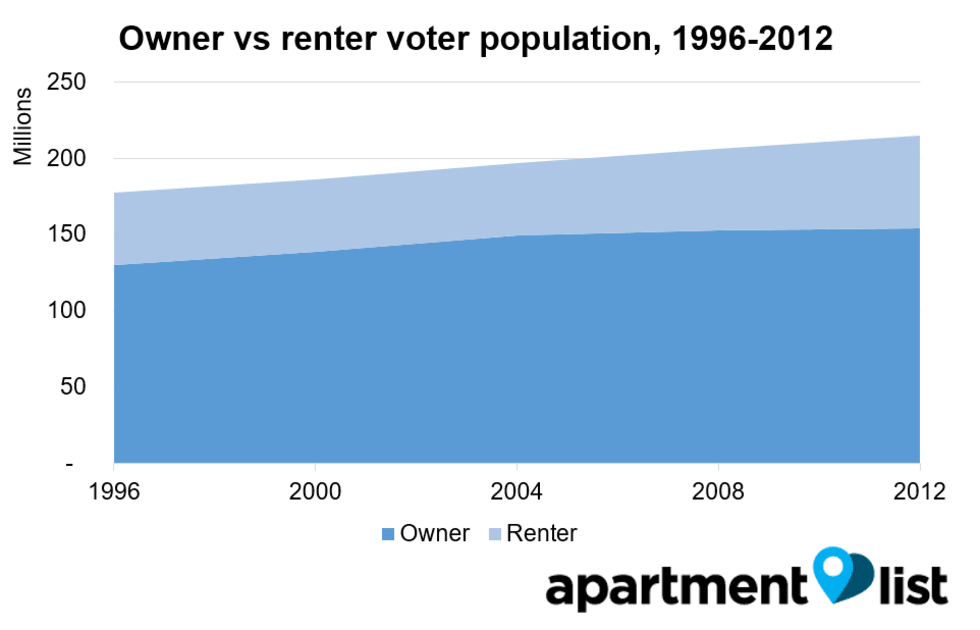

The size of the owner population swelled from 1996-2004, even as the renter population stayed stagnant. Following the Great Recession, however, that trend reversed - as the US homeownership rate fell, the size of the owner population barely increased, even as the renter population jumped nearly 30%.

The size of the owner population swelled from 1996-2004, even as the renter population stayed stagnant. Following the Great Recession, however, that trend reversed - as the US homeownership rate fell, the size of the owner population barely increased, even as the renter population jumped nearly 30%.

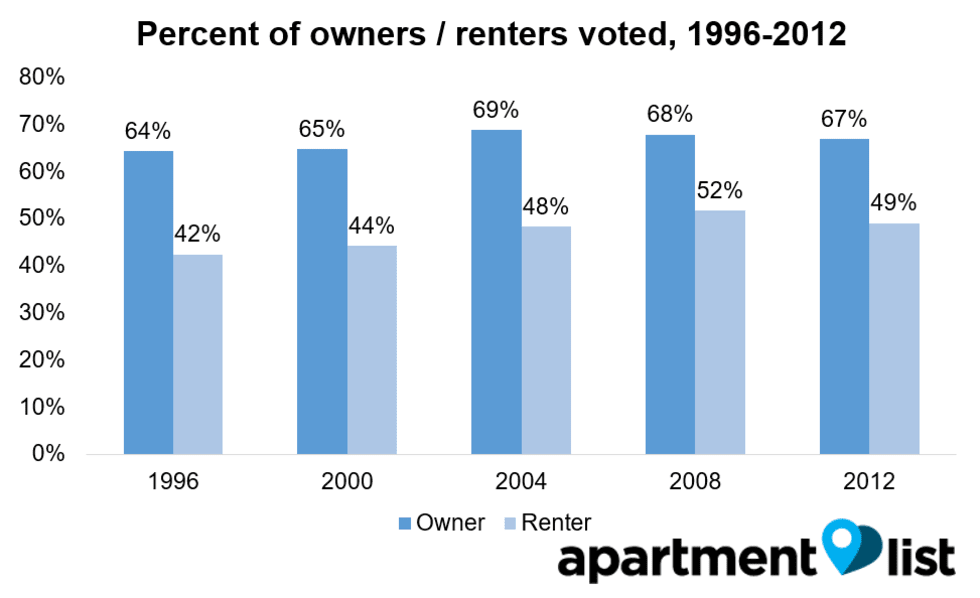

Voter turnout rates have also increased more rapidly among renters

Also, the voter turnout rate has increased rapidly among renters, rising from 42% to 49% over the 1996-2012 time period we examined. In contrast, it rose only 3% among homeowners. Part of this may be because of Obama's success at appealing to millennials (it remains to be seen whether Hillary can do the same), but young voters are becoming increasingly engaged with politics.

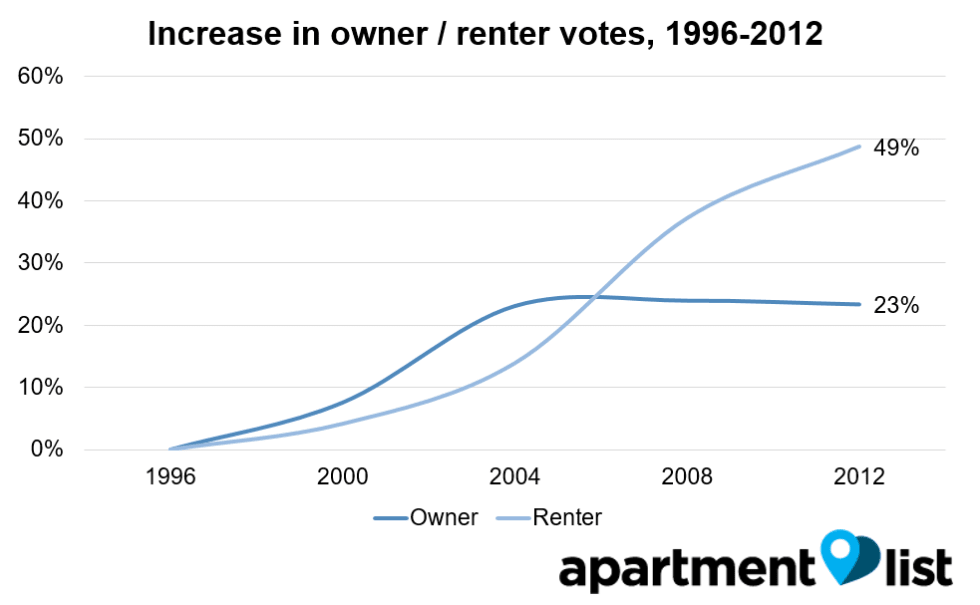

Renter votes have increased 49% since 1996, but owner votes only increased 23%

As a result, the number of votes cast by renters has increased more quickly than homeowner votes, especially since in the most recent decade. Their overall share of votes remains relatively small (29% in 2012), but if recent trends hold, it's quite possible that renters could form 1/3 or more of the voter population in the near future.

What to do?

There are some who would insist that things will never change; that their vote doesn't matter, and affordability will always be an issue. While it is certainly true that longtime issues may persist despite an increase in voter participation, one thing is certain: the diversity and voting power of renters, whether withheld or put forth, has a significant long-term impact on housing nationwide.

Renters may not think they hold a lot of electoral power, but with the population of voters increasing and more young citizens becoming involved in politics, the future could look quite different.

Share this Article