Poverty in the Suburbs: Are Cities Prepared to Deal With the Growing Problem?

There is growing concern about poverty in the suburbs, known as the “suburbanization of poverty.” In order to better understand the changing geography of poverty, Apartment List analyzed national and metro level data from the Joint Center on Housing Studies at Harvard University a**n**d found that, while poverty has grown in both suburban and urban areas, it is increasing faster in the suburbs.

The Apartment List findings, revealing increasing suburban poverty in metros nationwide-- including Chicago, Houston, Charlotte and Orlando--raise serious questions about whether cities are prepared to confront the issues raised by increasing suburban poverty.

Over a 15-year period from 2000 to 2015, the Harvard data reveals, poverty increased across the United States in neighborhoods within metropolitan areas classified as “low-density,” “medium-density” and “high-density,” as well as in rural areas outside metros. While a larger share of the country’s poor population lives in dense urban areas than any other neighborhood type, poverty is becoming increasingly suburban, as the share of the poor population in low-density and medium-density urban areas, considered “suburban,” grows.

The majority of the poor population living in high-poverty neighborhoods no longer lives in dense urban areas. In 2000, about 51 percent of the poor population living in high-poverty neighborhoods resided in dense urban areas, but by 2015, this figure dropped to about 43 percent. Furthermore, in 85 percent of metros, a smaller share of the population living in high-poverty neighborhoods resided in dense neighborhoods in 2015, compared to 15 years earlier.

Overall, the U.S. poverty rate has increased to 13.5 percent in 2015 from 11.3 percent in 2000. In 2010, during the Great Recession, the poverty rate reached a high of 15.1 percent, but has been declining since. Poverty is also becoming more concentrated as the population living in high-poverty neighborhoods, defined as neighborhoods with at least 20 percent of the population living in poverty, has grown. Over 15 years, the poor population in high-poverty neighborhoods grew by 70 percent, much faster than the overall poor population, which grew by 30 percent over the same period.

Over the 15 years, the number of high-poverty neighborhoods, defined as those with 20 percent or more of the population living below the poverty line, has increased to 21,328 neighborhoods from 13,426 neighborhoods, or an increase of about 8,000 neighborhoods. The poor population in dense urban areas has not decreased. Rather, the poor population living in less dense areas has increased.

Introduction

Poverty is generally perceived as an urban problem, characterized by poor, black “inner cities,” but, in reality, poverty is also a problem in suburban and rural areas. Suburban poverty is not a new problem, but poverty has been growing faster in less dense urban areas, catalyzed by the Great Recession in the late 2000s and early 2010s.

In the 1980s and 1990s, dense urban areas experienced high crime and poverty rates, and middle-class families fled to less dense urban areas for economic opportunities and jobs. There are no longer enough good-paying, low-skilled jobs in the suburbs to keep families out of poverty.

Another reason poverty is more concentrated in the suburbs has to do with the availability of more affordable housing in less dense areas. As inner-city neighborhoods gentrify and homes become more expensive, poor families are pushed out of dense urban centers into less dense suburbs. Still, while a select number of neighborhoods in urban cities are gentrifying rapidly, pushing out poor residents, many high-poverty neighborhoods remain in large cities. Joe Cortright, an urban economist at City Observatory, writes that “the real story of neighborhood change in the United States is the persistence and spread of concentrated poverty.”

Poverty in low-density and medium-density areas provides new challenges, as these areas often lack jobs, transportation and services. While poverty has grown in the suburbs, social safety-net programs aimed at reducing poverty are primarily located in urban centers. Although some regions have begun to address the suburban poverty crisis, poor families tend to be more spread out in the suburbs making them harder -- and more expensive -- to reach.

In order to better understand the crisis of suburban poverty, Apartment List analyzed data from the 2017 State of the Nation’s Housing report by the Harvard Joint Center for Housing Studies. The study uses U.S. Census tracts to represent neighborhoods, categorizing tracts within MSAs as low-density, medium-density and high-density areas. The study focuses on high-poverty neighborhoods, defined as neighborhoods with a poverty rate of 20 percent of higher.

The largest share of poor in high-poverty neighborhoods live in high-density urban neighborhoods, but the majority of poor in high-poverty neighborhoods now live in suburban or rural areas.

| Neighborhood Type | 2000 | 2015 | Change |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dense Urban | 51.4% | 42.7% | -8.7% |

| Medium Dense Urban | 21.5% | 25.3% | 3.8% |

| Least Dense Urban | 10.1% | 15.2% | 5.0% |

| Outside MSA | 16.9% | 16.8% | -0.1% |

| Total | 100.0% | 100.0% | 0.0% |

In 2000, the majority of the poor living in high-poverty neighborhoods was concentrated in dense urban areas. By 2015, the share had dropped by about 9 percentage points to 42 percent from 51 percent. A greater share of poor individuals and families living in high-poverty areas resided in medium-density and low-density urban areas, increasing to about 40 percent in 2015 from 32 percent in 2000, or by 3.8 percent and 5.0 percentage points, respectively. The share of the poor living in high-poverty neighborhoods in low-density urban areas increased the most over the past decade, but remains a relatively small share of those living in high-poverty neighborhoods, at only about 15 percent.

Number of high-poverty tracts in low-density urban areas increased by 123 percent between 2000 and 2015

Concentrated poverty provides additional burdens both for communities and individual residents. High-poverty neighborhoods create communities with serious crime, health and education problems. Apartment List looked at the change in high-poverty neighborhoods, defined as Census tracts where over 20 percent of residents live below the poverty line.

| Neighborhood Type | 2000 | 2015 | Percent Increase |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dense Urban | 6,473 | 8,666 | 33.9% |

| Medium Dense Urban | 3,013 | 5,313 | 76.3% |

| Least Dense Urban | 1,477 | 3,299 | 123.4% |

| Outside MSA | 2,463 | 4,050 | 64.4% |

| All Neighborhoods | 13,426 | 21,328 | 58.9% |

Concentrated poverty remains prevalent in cities, suburbs and rural areas with about 8,000 more high-poverty tracts compared to 15 years ago, representing a 59 percent increase. From 2000 to 2015, the number of high-poverty neighborhoods grew in all neighborhood types -- low-density, medium-density, high-density and outside of Metropolitan Statistical Areas (MSAs).

Although dense urban areas comprise the largest number of high-poverty neighborhoods, the growth in high-poverty neighborhoods has been more rapid in medium-density and low-density urban areas, as well as in rural areas. The largest share of high-poverty neighborhoods remained in dense urban areas, but this share shrank. In 2015, about 40 percent of high-poverty neighborhoods were in dense areas, down from 48 percent in 2000.

The number of high-poverty neighborhoods in medium-density and low-density urban areas grew fastest, by 76 percent and 123 percent, respectively. In absolute terms, the largest increase in high-poverty tracts was in medium-density urban areas, followed by high-density urban areas. Although the largest share of high-poverty tracts are still located in high-density urban areas, suburban poverty is becoming increasingly common.

Largest increase in number of total high-poverty neighborhoods in Rust Belt and Southeast, compared to similar-sized metros

Furthermore, Apartment List learned that, while most large metros saw increases in the total number of high-poverty tracts, metros in the Rust Belt and Southeast had particularly large increases in the number of high-poverty neighborhoods compared to other similar-sized metros.

Chicago experienced the largest increase in its total number of high-poverty neighborhood, rising to 645 neighborhoods in 2015, from 429 neighborhoods in 2000, or a total increase of 216 neighborhoods. This was about the same increase seen in Los Angeles, New York and Philadelphia, combined.

Detroit is the twelfth-largest metro, but ranked second for the increase in high-poverty neighborhoods. The total number of high-poverty neighborhoods in suburban and urban Detroit increased by 203 over the 15-year period, to 450 neighborhoods from 247 neighborhoods.

Atlanta (No. 2), Dallas (No. 3), and Phoenix (No. 4) also ranked in the top five for the largest growth in the number of high-poverty tracts overall, while coastal metros, such as New York (64 new high-poverty neighborhoods), Washington, DC (23) and Los Angeles (67), fared better, given their large population size.

Cleveland, a mid-sized Rust Belt metro, experienced a large increase in its total number of suburban and urban high-poverty neighborhoods, with 90 more high-poverty neighborhoods in 2015 compared to 2000. San Antonio, a slightly larger metro than Cleveland, only saw an increase in the number of total high-poverty neighborhoods by 24 neighborhoods over the same period.

Florida metros experienced particularly large increases in their total number of high-poverty neighborhoods, relative to other similar-sized metros, for example, increasing by 140 neighborhoods in Miami, 113 neighborhoods in Tampa and 91 neighborhoods in Orlando.

Of the total population living in high-poverty neighborhoods, a higher share was in suburban areas in 2015, compared to 2000.

| Metropolitan Area | 2000: Share in Suburban | 2015: Share in Suburban | Change |

|---|---|---|---|

| Akron, OH | 52% | 70% | 19% |

| Albany-Schenectady-Troy, NY | 15% | 17% | 2% |

| Albuquerque, NM | 61% | 59% | -2% |

| Allentown-Bethlehem-Easton, PA-NJ | 20% | 23% | 3% |

| Atlanta-Sandy Springs-Roswell, GA | 72% | 82% | 9% |

| Austin-Round Rock, TX | 44% | 46% | 2% |

| Bakersfield, CA | 61% | 69% | 8% |

| Baltimore-Columbia-Towson, MD | 11% | 13% | 2% |

| Baton Rouge, LA | 79% | 83% | 3% |

| Birmingham-Hoover, AL | 81% | 87% | 6% |

In order to understand changes in concentrated poverty, Apartment List looked at the share of the population living in high-poverty neighborhoods in each density type. The share of the total population living in tracts with poverty rates of 20 percent or higher increased in all metros from 2000 to 2015, but the distribution by neighborhood type changed over the period, with more in suburban neighborhoods.

The total population living in high-density poor neighborhoods increased in all but 12 metros, but in most metros a smaller share of the population in high-poverty neighborhoods lives in dense tracts. In 85 percent of metros, the share of the population living in high-poverty suburban neighborhoods increases, while the population in high-poverty urban neighborhoods decreased.

In 54 percent of metros, a larger share of the population living in high-poverty neighborhoods now lived in medium-density tracts, than in 2000. Of those living in high-poverty neighborhoods, a greater share lived in low-density areas in 80 percent of metros in 2015.

Although most metros have a larger total population in medium-density and dense high-poverty tracts, many metros saw large increases in the total population living in high-poverty low-density areas. For example, in Nashville, 11 percent of the population in high-poverty neighborhoods lived in low-density tracts in 2000, but, over the past 15 years, that figure increased to 35 percent.

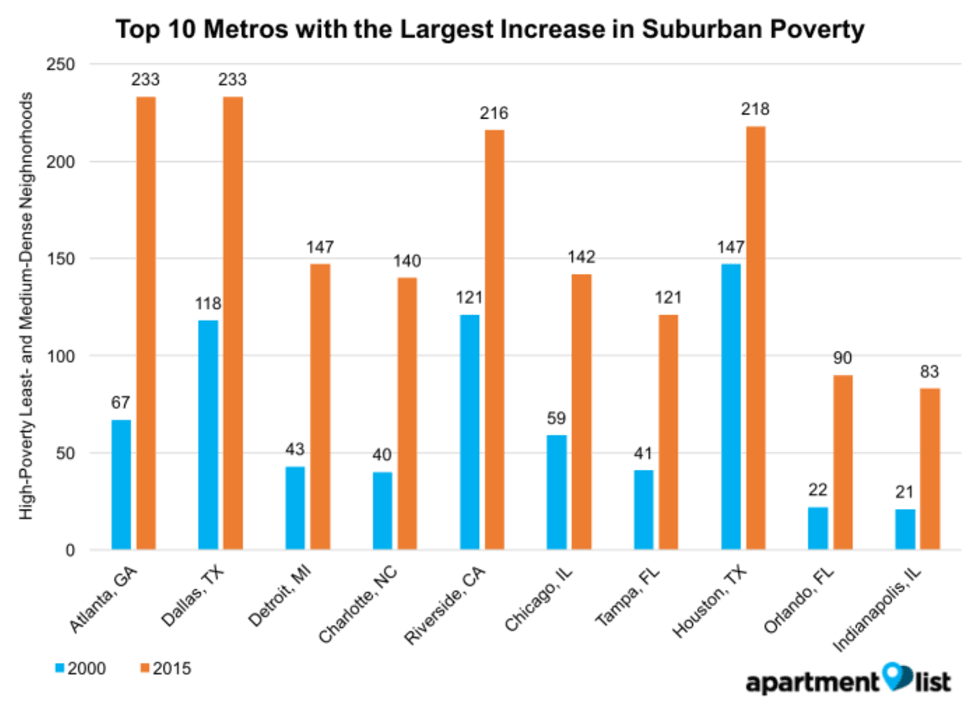

Six out of 10 metros with the largest increase in suburban poverty are located in the South

To evaluate the impact of suburban poverty on specific metros, Apartment List examined increases in the number of low-density and medium-density neighborhoods with high-poverty populations between 2000 and 2015. We identified the top 10 metros with the largest numerical increase in their suburban high-poverty neighborhoods and found that the metros with the highest increase in the number of neighborhoods marked by suburban poverty tended to be less dense metros overall. Many of these metros, primarily located in Southern states, such as Georgia, Texas, Florida and South Carolina, experienced rapid and sprawling population growth.

No. 1 Atlanta and No. 2 Dallas had the largest increase in the number of high-poverty suburban neighborhoods, as well as the highest overall number of high-poverty suburban neighborhoods.

The number of high-poverty suburban neighborhoods in No. 1 Atlanta rose by 198 percent to 233 neighborhoods in 2015, compared to 67 neighborhoods in 2000, an increase of 166 neighborhoods.

The number of high-poverty suburban neighborhoods in No. 2 Dallas went up by 103 percent over the same 15-year period, to 233 new high-poverty suburban neighborhoods in 2015 from 118 neighborhoods in 2000, or an increase of 115 neighborhoods.

No. 3 Detroit is the twelfth-largest metro, but ranked third for the increase in high-poverty neighborhoods, increasing to 147 neighborhoods in 2015 from 43 neighborhoods in 2000.

No. 4 Charlotte, N.C., is the 24th largest metro in the United States, and the smallest metro out of the 10 metros with the largest increase in suburban poverty. Charlotte saw an increase in high-poverty neighborhoods of 100 neighborhoods, to 140 neighborhoods in 2015 from 40 neighborhoods in 2000.

One California metro, No. 5 Riverside, Calif., east of Los Angeles, saw an increase in the number of high-poverty neighborhoods, topping out at 216 high-poverty neighborhoods in 2015, compared to 121 high-poverty neighborhoods in 2000.

Chicago, No. 6, saw an increase in high-poverty suburban neighborhoods of 83 neighborhoods, but the majority of high-poverty neighborhoods in Chicago remain in dense urban areas. In 2015, there were 503 high-poverty urban neighborhoods and 142 high-poverty suburban neighborhoods.

The number of high-poverty neighborhoods in No. 7 Tampa increased by 195 percent over the 15-year period, from 41 high-poverty suburban neighborhoods to 121 high-poverty suburban neighborhoods.

No. 8 Houston experienced an increase of 69 new high-poverty suburban neighborhoods during the 15-year period, rising to 218 high-poverty suburban neighborhoods in 2015, from 147 similar neighborhoods in 2000.

In Florida, No. 9 Orlando saw the largest percent increase in high-poverty suburban neighborhoods of the cities in the top 10. Orlando experienced a 310 percent increase in high-poverty suburban neighborhoods during the 15-year period with 90 such neighborhoods in 2015, up from 22 similar neighborhoods in 2000.

Finally, mid-sized Rust Belt metros, such as No. 10 Indianapolis (62), also saw large increases in the number of high-poverty suburban neighborhoods, compared to other similar sized metros.

Is Suburban Poverty Overhyped?

The suburbanization of poverty has become a common narrative, especially since the start of the Great Recession. In 2010, the Brookings Institution released a report, The Suburbanization of Poverty: Trends in Metropolitan America, 2000 to 2008. Its researchers concluded that “suburbs saw by far the greatest growth in their poor population and by 2008 had become home to the largest share of the nation’s poor.” In the report, Brookings predicted the trend would continue, representing an “ongoing shift in the geography of American poverty.”

Data from subsequent years reveal the shift of poverty towards suburban areas continues, in part mirroring a general population shift to the suburbs. In the City Observatory report, Cortright, the urban economist, argues the story of “rich cities, poor suburbs” is exaggerated, as “it is still the case that the poor are disproportionately found in or near the city center, and the wealthy live in suburbs.” While poverty is growing in suburban areas, suburban poverty becoming more common than urban poverty would require this trend to continue for decades.

Suburban poverty is not new. Scott Allard, author of Places in Need**,** a book published in June 2017, argues in a City Lab interview that “one of the realities in the rise of suburban poverty is that it hasn’t corresponded with a decrease in urban poverty. We just lack the capacity of tackle the problem in suburban areas.” We’ve built extensive nonprofit and government programs to try to mitigate urban poverty because it’s been a problem for so long, but most metros don’t have the infrastructure or resources to handle suburban poverty. In many suburban regions, nonprofits have a hard time attracting charitable funding because poverty is thought of as an urban epidemic. Furthermore, it’s hard to reach the suburban poor, and programs require collaboration across more local governments and organizations.

While the suburbanization of poverty has become an increasing reality over the past decade, poverty has not disappeared from urban areas. In fact, the number of high-poverty tracts is growing in rural, suburban and urban America. With stagnating wages, rising home prices and rents and higher concentrations of high-paying jobs in a few metros, we need to worry about poverty in all parts of the country.

Expanding our awareness of poverty outside of urban cores is necessary to create innovative programs, both public and private, to pull families out of poverty and revitalize high-poverty neighborhoods throughout the entire country.

Share this Article