The Suburban Rent Boom Has Been a Constant Throughout the Pandemic

Introduction

The past two and half years have been the most tumultuous time for the rental market in recent memory. Much of that tumult can be traced back to the way that the pandemic has changed the ways that we live and work. In the earliest phases of the pandemic, many of the nation’s large cities saw sharp rent declines as a subset of renters with newly remote working arrangements moved away from expensive downtown areas that had temporarily lost their vibrancy, in search of more space in the surrounding suburbs. At the same time, widespread job losses also forced many workers to give up leases they could no longer afford. In the time since, big city rent prices have bounced back as employment has rebounded and return to work plans have begun to materialize. But it’s still the suburbs that have continued to see the fastest rent growth. Heightened demand for suburban rentals could continue as an ongoing trend, particularly as a sizable share of the workforce maintains some level of remote work flexibility, and as the large Millennial population continues to age into their “settling down” phase. In this report, we explore in detail how this trend has been playing out in our rent data.

In major metros across the U.S. rents have been growing faster in the suburbs than in the urban core

Analyzing our rent estimates across 39 large and medium-sized metropolitan areas, we find that since March 2020, rents in the suburbs of these metros have grown by 27.2 percent, on average, substantially outpacing the 19.8 percent average rent growth in the core cities that they surround.12

This gap began to emerge quickly after the pandemic’s onset. With most urban amenities closed or operating in limited capacity during the lock-down phase of the pandemic, many workers who lost jobs or who no longer needed to be close to an office decided that it was no longer wise to pay a premium for downtown rentals. As existing renters gave up their leases without new renters to take their places, rents in core cities were discounted. This was especially true in the nation’s priciest cities, such as San Francisco, Seattle, Boston, and New York City, all of which saw their median rents plummet by at least 20 percent by the end of 2020. On average, rents in the core cities that we analyzed fell by 4.6 percent from March through December of 2020. Meanwhile, rents in the suburbs of these metros ticked up slightly, rising by an average of 0.7 percent.

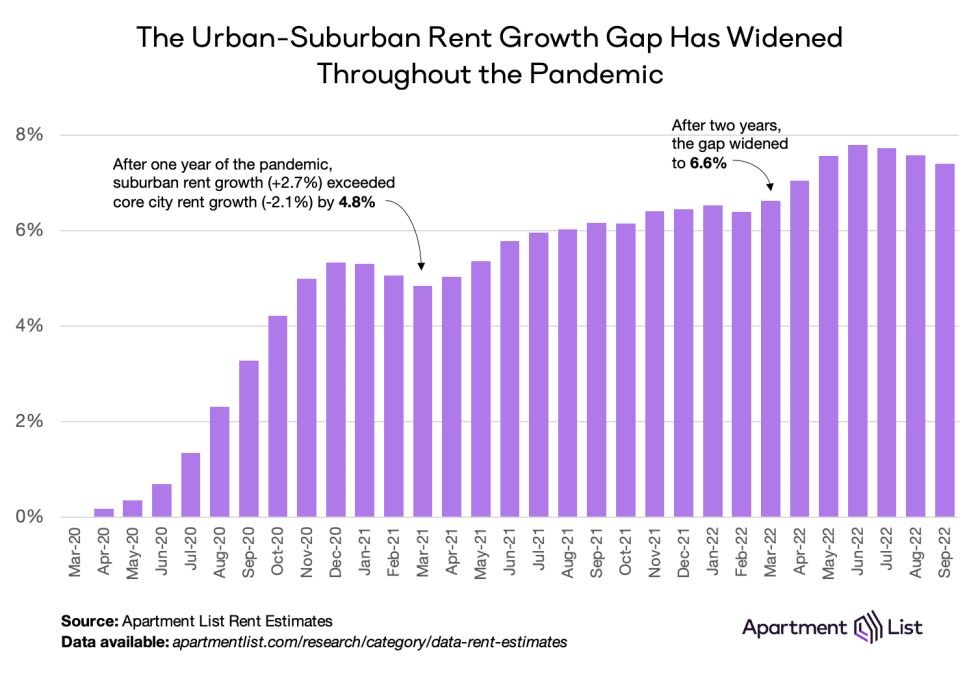

Conditions quickly changed in 2021 – the large cities where rents had been falling quickly turned a corner and began sharp rebounds, leading to a temporary narrowing of the rent growth gap between core cities and suburbs in early 2021. But suburban rent growth then proceeded to outpace core city rent growth again, even as prices skyrocketed in both sets of cities, driven by tight supply colliding with a surge in demand. And while rent growth has cooled somewhat in 2022, it has continued at an elevated pace in both core cities and suburbs. Throughout the past year and a half, the rent growth gap between core cities and suburbs has, for the most part, been continuing to gradually widen, as can be seen in the chart above. The continuation of this trend indicates that this gap is not solely an artifact of early pandemic disruption.

There were signs of this divergence emerging even before the pandemic

In fact, if we extend the view of this analysis back even prior to 2020, we see signs that this trend may have been starting to emerge even before the pandemic’s onset:

Over the course of 2018, core city and suburban rents increased by the exact same amount, on average (3.7 percent). But in 2019, the average suburban rent growth of 3.1 percent solidly outpaced the 2 percent average growth of core cities. While this gap is fairly modest in comparison to what would come, it can be viewed as evidence that the pandemic may have accelerated an existing trend rather than start an entirely new one. The emergence of this shift toward the suburbs may reflect the changing preferences of the Millennial generation, who have been aging into the “settling down” phase of their lives in recent years. During the pandemic, a widespread shift toward remote work then made the suburbs an even more appealing option.

In large metros, the fastest rent growth is happening in the farthest-flung suburbs

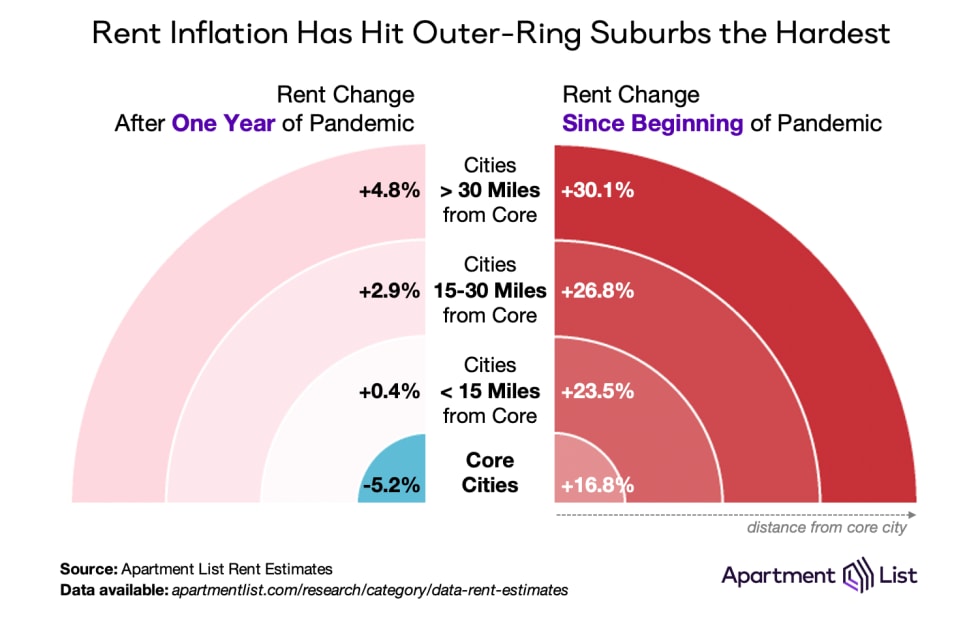

The impact of remote work on these changing preferences would seem to be validated by an additional finding that emerges when we break down our suburban rent data into more granular categories. Namely, the fastest rent growth since March 2020 has been occurring in the suburbs that sit furthest from the urban core. For the purposes of this analysis, we have limited the data to 13 large metros where we have robust rent estimates for a wide swath of suburbs at varying distances from the core city.

Among these 13 metros, the first year of the pandemic brought an average rent decline of 5.2 percent in the core cities. Over that same year, the outer-ring suburbs that sit more than 30 miles from the core city saw the fastest rent growth, with an average increase of 4.8 percent, roughly proportional to the decline in the core cities. Looking over the full pandemic period, rents in the core cities have risen by an average of 16.8 percent since March 2020. Over the same period, the near suburbs that lie within 15 miles of the core cities saw rents increase by 23.5 percent. Meanwhile, the mid-distance suburbs (15 to 30 miles from the core city) experienced rent growth of 26.8 percent, and the farthest flung suburbs that are more than 30 miles from the urban core have seen the fastest rent growth at 30.1 percent.3 In other words, rent growth has been progressively hotter moving outward in concentric rings from the urban core.

It seems highly likely that remote work is playing a role in this trend. Even as some companies have begun requiring employees to return to the office, many workers are still retaining the ability to work from home at least part-time. This sort of hybrid work arrangement is likely to alter decision making with regards to how far one is willing to live from the office. A long commute from the distant suburbs may seem much more reasonable if it only needs to be endured twice per week. It seems that some workers are choosing to forgo the convenience of being close to the city in favor of getting more space at a lower price point. And given that far flung suburbs have less rental inventory than large cities, these markets are ill-prepared for an influx of new renter households, leading to the disruption reflected in our rent growth estimates.

To help better visualize this shift in rental demand toward the outer suburbs, the following sets of maps plot city-level rent growth over the past year and over the full course of the pandemic for three of the metros where the divergence has been most stark.

As mentioned above, Seattle experienced one of the nation’s sharpest rent declines in 2020. One year after the pandemic’s onset in March 2021, rents in Seattle proper were down by 17.8 percent. The close suburbs that are less than 15 miles from downtown also saw rents fall, but much less sharply, with an average decline of 4.9 percent. Meanwhile, the middle- and outer-ring suburbs saw rents rise over this period, increasing by an average of 4.2 percent among the suburbs lying 15 to 30 miles from the urban core, and by 5.1 percent in the far suburbs that sit more than 30 miles out. In the time since, prices have bounced back in the core city, with rents in Seattle-proper now 6 percent higher than they were in March 2020. But even as some renters have moved back downtown, the Seattle suburbs have boomed much faster, with rents up by 23.8 percent since the start of the pandemic.

Similar to Seattle, Los Angeles also experienced a decline in core city rents in the first year of the pandemic followed by a quick rebound. The median rent in the city of Los Angeles is currently 9.4 percent higher than it was in March 2020. But here too we see a clear pattern of increasingly faster rent growth moving outward in concentric rings from the core city. In the near suburbs of Los Angeles, rents are up by 13.3 percent since the start of the pandemic; in the mid-distance suburbs they are up by 23.9 percent; and in the long-distance suburbs, they are up by 26.9 percent.

The Atlanta metro differs from the two examples above in that the core city did not experience any notable rent decline in the early-pandemic. From March 2020 to March 2021, rents in Atlanta-proper were essentially flat (+0.7 percent). But over that same period, rents in the Atlanta suburbs jumped by 7.2 percent. Fast-forwarding to today, rents in Atlanta-proper are up by 21.2 percent since March 2020, roughly inline with the growth in our national rent index over that period (+23.4 percent). Meanwhile, rents in the Atlanta suburbs are booming substantially faster, and are up by 35.8 percent since the start of the pandemic. Here again, the fastest growth is happening in the farthest suburbs, with a whopping 40.3 percent increase among the suburbs that are 30 miles or more from the core city.

33 of 39 metros in our analysis have had faster rent growth in the suburbs since March 2020

The case studies above represent three of the metros where the divergence between core city and suburban rent growth has been most stark. But even if we expand our view, this is a trend that we observe in the overwhelming majority of the metros that we analyzed. The chart below plots core city vs suburban rent growth since March 2020 at the metro level. If rents in the core city of a given metro were growing at the exact same rate as the metro’s suburbs, the marker for that metro would fall directly on the diagonal line running across this chart. In fact, we see that the markers for 33 of the 39 metros in our study fall above the horizontal, indicating that rents are rising faster in the suburbs than in the core cities.

The single widest gap is actually found in the Cleveland metro. Cleveland-proper has seen rents increase by a total of just 7.3 percent since the start of the pandemic; meanwhile, the metro’s suburbs have seen rent prices spike by 31.4, on average. The top five metros with the starkest divides is rounded out by Portland (7.6 percent in the core city vs 29.3 percent in the suburbs), Seattle (6 percent vs 23.8 percent), Atlanta (21.2 percent vs 35.8 percent), and Los Angeles (9.4 percent vs 23.2 percent).

At the other end of the spectrum, the nation’s largest metro is one of the few to buck the trend. After a sharp decline in the early pandemic, New York City rents have actually seen the nation’s fastest rent growth over the past year and a half, and are now up by 18.3 percent since March 2020. The metro’s suburbs, however, are up by just 14.2 percent over the same period. Charleston, San Jose, Riverside, Las Vegas, and Tampa are the only other metros where core city rent growth has exceeded suburban rent growth over the past two and a half years. Notably, three of these metros – Tampa, Las Vegas, and Riverside – rank among the top ten for fastest metro-wide rent growth over this period. It seems that cross-metro migration patterns may be offsetting the intra-metro shifts in these markets, as the core cities of these metros have experienced an influx of demand from renters fleeing more expensive parts of the country.

Conclusion

The past two and half years have ushered in rapid changes to the ways that we live and work, driving significant shakeups to the housing market. One such disruption has been a spike in demand for suburban rentals. Even as large core cities have rebounded strongly from early-pandemic declines, rent growth has continued to be fastest in the suburbs. Even before the pandemic, increasingly unaffordable housing costs close to the urban core had been pushing more and more renters to the far peripheries of the nation’s large metro areas, resulting in a proliferation of “super commuters". City living has proven resilient, and will surely retain its appeal going forward, but with a meaningful share of the workforce poised to maintain at least partial remote work flexibility going forward, the far flung suburbs of large metros may continue to experience elevated housing demand going forward. Even if these workers are only commuting part-time, this type of sprawl is at odds with making progress on climate goals. Crucially, spiking demand in the far suburbs appears to have more to do with affordability than with geographic preference – this trend should only emphasize the need for sustainable development with easy transit-oriented access to the urban core.

- This analysis is restricted to metropolitan areas for which Apartment List’s city-level rent estimates include data for the metro’s core city as well as at least three suburban cities. For the purposes of this study, we define the “core city” as the single largest city in the metro by population, while all other cities in the metro are considered “suburban.”↩

- For each metro in our study, core city rent growth is synonymous with our city-level rent estimates for the metro’s core city, as defined above. Suburban rent growth at the metro-level is estimated as a population weighted average of all suburban cities for which we have data in the given metro. National results are aggregated up from these metro-level estimates, taking a straight average of the core city and suburban rent growth estimates across the 39 metros included in the study.↩

- Note that for this purpose, distances are calculated as straight-line distances between the centroid of each suburb and the centroid of its corresponding core city. The average commuting distance from each suburb to its corresponding core city is farther than than these straight-line distances.↩

Share this Article